For some artists in “The Shape of Power,” it isn’t enough to reveal forgotten histories. They actively confront the laws and policies that have defined who belongs in public life. Through their work, they expose how race, citizenship, and identity are not just matters of legislation but lived realities. These sculptures don’t just represent the past; they challenge the frameworks that continue to inform our present.

Maggie Thompson, Family Portrait, 2013. Image courtesy of the Minneapolis Institute of Art.

In Maggie Thompson’s Family Portrait (2012), woven tapestries visualize the government-imposed system of “blood quantum,” a racial classification used to define Indigenous identity and citizenship. These laws restricted the number of people who could legally qualify as Native, thereby limiting who was eligible for the benefits and protections outlined in treaties with the United States government. By representing her family through blocks of red and white, the artwork challenges notions of racial authenticity and exposes the arbitrary nature of quantifying identity. In an era of increasing surveillance and biometric data collection, Family Portrait raises timely questions: Who gets to define identity, and on what terms?

Sonya Clark, Octoroon, 2018, Canvas and thread, Chrysler Museum of Art, 2020.4, Image courtesy of the artist and Lisa Sette Gallery

Reinterpreting the U.S. flag in Octoroon (2018), Sonya Clark braids cornrows into black thread at the top left of the canvas, which then unravels into loose strands. The title references a derogatory racial classification that categorized individuals as Black if they had even “one drop” of African ancestry. The “one drop” rule created the conditions for hereditary slavery. In a political moment where debates over racial categories, voter ID laws, and the appropriateness of various hairstyles and textures are prevalent, Octoroon lays bare the constructed nature of race and honors the histories of resistance embedded in Black cultural practices, such as hair braiding.

Ed Bereal, America: A Mercy Killing, 1966-1974, mixed media. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Museum purchase. Image courtesy of the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

Ed Bereal’s kinetic sculpture, America: A Mercy Killing (1966-74), presents a dystopic parody of American life. A collapsing class structure, upheld by the bodies of enslaved and Indigenous peoples, plays out atop an American flag, with money, media, and military forces controlling the scene above. Given the context of mounting economic inequality and ongoing debates about access to desirable spaces, Bereal’s work remains unsettlingly relevant.

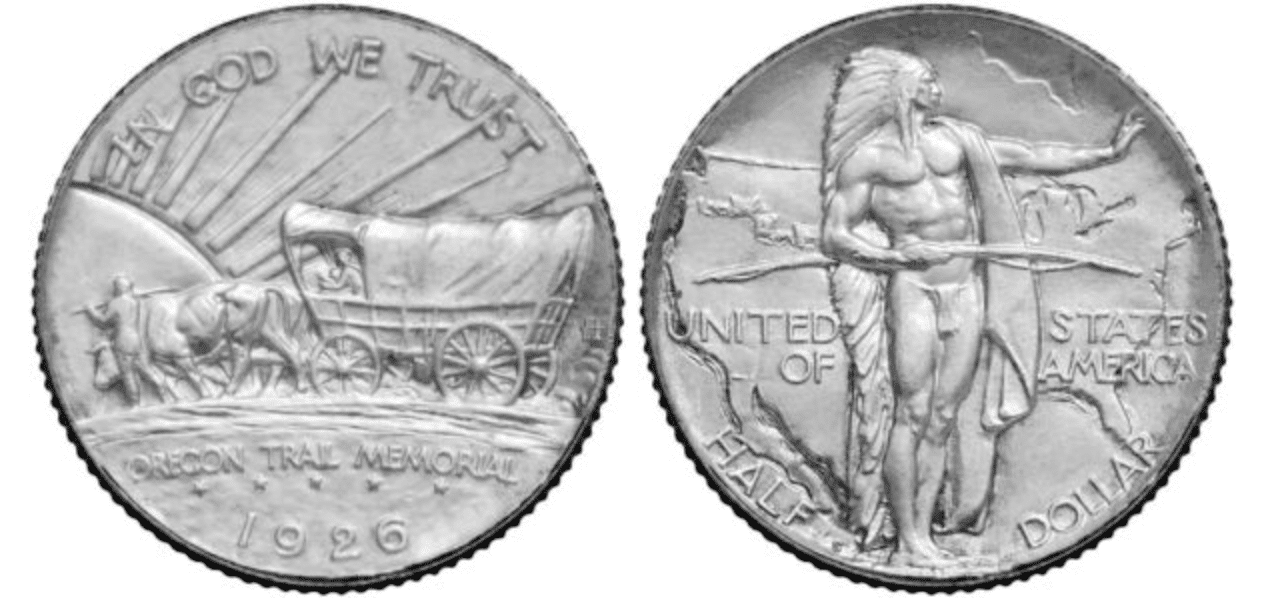

Minted between 1926 and 1937, the Oregon Trail Commemorative Half Dollar, created by James Earle Fraser and Laura Gardin Fraser, glorifies westward expansion and federal land giveaways that dispossessed Indigenous communities. The obverse side features settlers heading westward, while the reverse romanticizes a mostly nude Native figure superimposed over a U.S. map. At a time when land acknowledgments and Native land reclamation movements are gaining momentum, the coin serves as a reminder of how the federal government used even small-scale objects to embed settler colonial mythologies.

Gabriela Muñoz and M. Janea Sanchez, Labor—Maty& Doña Higinia, 2016-20, serigraphs on bricks handmade by DouglaPrieta Trabajan of Colonia Ladrillo in Agua Prieta (Sonora, Mexico), 30 x 49 x 6 in., Wheelwright Museum of the American Indian, Santa Fe, New Mexico, 2021.20.00. Photo by Albert Ting.

Constructed from handmade bricks screen-printed with portraits of women from the DouglaPrieta Trabajan collective, M. Jenea Sanchez and Gabriela Muñoz’s Labor (2016-20) reclaims the image of a wall. Created in response to Donald Trump’s calls for expanded border militarization, this wall symbolizes not fear and division, but resilience, labor, and shared protection. In a time when immigration policy continues to shape public discourse, this piece reframes the narrative: What if walls could hold, rather than exclude?