What does it mean to belong in America?

That’s the question at the heart of On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America, a groundbreaking exhibition at the Peabody Essex Museum (PEM) in Salem, Massachusetts. When it opened in 2022, the installation was intended to be a thought-provoking exploration of American identity and its evolution. Three years later, amidst discussion and debate about America, what the country is, and what it should be, its themes feel more urgent. On This Ground invites visitors to reflect on community, representation, and how people define belonging.

“We wanted to reflect both the diversity and complexity of America,” says Sarah Chasse, co-curator of the show. “And that requires seeing different histories as part of the same American story.”

As conversations around American belonging, memory, and cultural ownership continue to intensify, On This Ground offers a timely reminder that belonging is not granted—it is created, questioned, and redefined, over and over again. Through collaboration, community engagement, and storytelling, this exhibition challenges us to see identity not as a fixed point, but as a living narrative we each have a responsibility to shape.

Belonging is about feeling connected, whether to a family, a place, a community, or a nation. Whether that nation is the United States or the Cherokee Nation, or perhaps both.

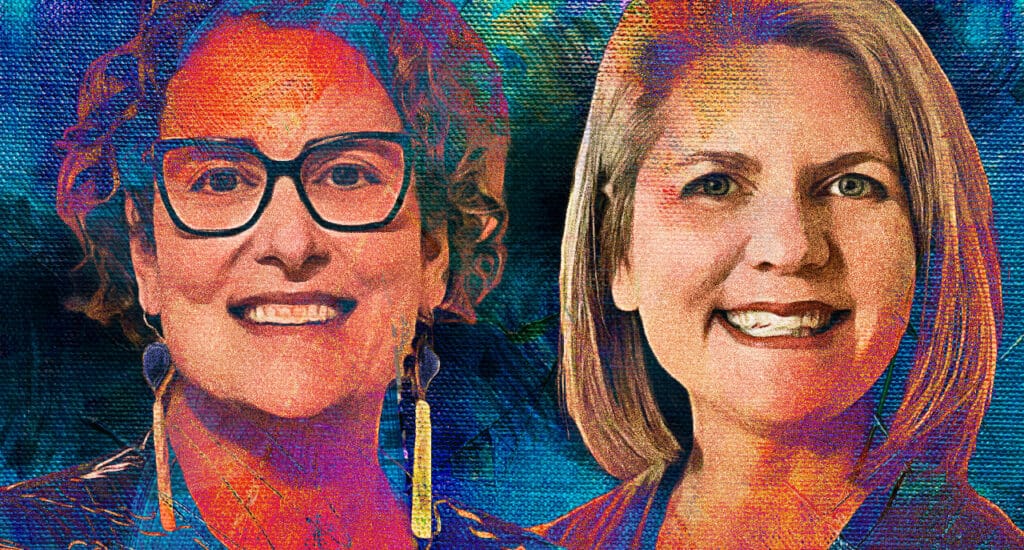

Karen Kramer, The Stuart W. and Elizabeth F. Pratt Curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture, Peabody Essex Museum and Sarah Chasse, Curator-at-Large, Peabody Essex Museum. Art by Adonis Durado.

When curators Karen Kramer and Sarah Chasse began imagining On This Ground: Being and Belonging in America, they weren’t just designing an exhibition—they were interrogating the foundations of American identity itself. Their effort led to something unprecedented: merging those collections not just physically, but conceptually. The result is a 10,000-square-foot installation spanning 10,000 years, where Native and non-Native artworks are presented on equal footing, woven together through powerful themes. “‘Being’ is evocative of our essential humanity and worldview,” says Chasse. “‘Belonging’ is about feeling connected, whether to a family, a place, a community, or a nation. Whether that nation is the United States or the Cherokee Nation, or perhaps both.”

For Kramer, who serves as the Stuart W. and Elizabeth F. Pratt Curator of Native American and Oceanic Art and Culture, the goal was to “challenge and expand understandings of American identity.” That meant going beyond inclusion and confronting the erasure baked into art institutions themselves. “We were very committed to Native art being understood on its own terms, not just in service of illustrating an aspect of American art and history,” she says.

The curatorial team, which included Lan Morgan, former Native American fellows, and three cohorts of Native American Summer Fellows, worked collaboratively to build an experience that examines tensions, contradictions, and overlooked truths. That includes narratives often missing from public memory, such as George Washington’s military campaign against the Haudenosaunee people, whose villages were burned to the ground in 1779. A multimedia piece by Alan Michelson (Mohawk) projects maps and documents onto a bust of Washington, asking visitors to reconsider who gets to be called a “founding father.”

But On This Ground also looks forward. It offers a continuous link between past and present, highlights Indigenous resilience, and invites everyone to reconsider what American art is—and who it’s for. “This installation explores vibrant expressions of what it means to belong and not belong,” Chasse says. Kramer says the community feedback has been deeply affirming: “‘We see ourselves.’ ‘Finally! We are seen.’ This has been one of the most gratifying aspects of the installation.” Ultimately, the show argues that belonging isn’t a fixed status. It’s a question that must be continually re-asked and re-imagined. “Amanda Gorman’s poem at the entrance reminds us that America’s story is still being written,” says Kramer. “I hope this installation inspires people to feel more responsibility to the land, to each other, and to the stories we choose to carry forward.”

You have to know what it’s like to feel like an outsider to truly understand what it means to belong.

Marie Watt

Artist Marie Watt, a member of the Turtle Clan of the Seneca Nation of Indians, believes the idea of belonging can’t be separated from connection—to people, land, stories, and even to the unseen forces that shape everyday life. “I think you have to know what it’s like to feel like an outsider to truly understand what it means to belong,” she says. “Belonging is complicated.”

That truth forms the foundation of Watt’s large-scale textile installation Companion Species: Cosmos, Sunrise, Flint, a community-driven piece created through a series of sewing circles. The gatherings invited neighbors, friends, and strangers to sit together, sew by hand, and share stories. The result: a vibrant, collaborative textile filled with layered embroidery, ancestral references, and poetic inscriptions. “In some ways, the artwork is an embodiment of a bunch of hands and voices coming together across social, economic, generational, and cultural experiences,” Watt explains. “That’s reflective of the beauty and complexity of American identity.”

Watt, who is based in Portland, Oregon and holds degrees from Willamette University, Yale University, and the Institute of American Indian Arts, is widely known for her use of reclaimed blankets and other textile materials as vessels for her storytelling. Much of her art stems from her Indigenous heritage as well as her background in printmaking and sculpture, blending traditional craft with intriguing concepts. Her title for Companion Species draws from the question that drives much of her work: What would the world look like if we considered ourselves companion species?

Inspired by the Haudenosaunee creation story, in which Sky Woman is helped by animals as she falls to Earth, Watt honors the belief that animals were our first teachers, and that all beings, from celestial bodies to cornfields, are part of the same web of belonging. In Companion Species, embroidered words flow across the textile surface, such as lyrics from Marvin Gaye’s What’s Going On, the names of Seneca clan animals, and translations of Indigenous place names from around Portland and the Northeast. “I employ text because language is loaded and uncomfortable,” she says. “Recontextualizing it opens up new meanings.”

The timing of the work’s showing in On This Ground feels especially pointed. “The social and political themes of this moment feel familiar, cyclical, and generationally pressing,” says Watt. “I feel a sense of urgency when it comes to altering behavior and creating initiatives to protect the planet now and for future generations.” Yet stitched into her work is the hope that people will see themselves reflected in the piece, and that the very act of gathering can move humans toward “interconnectedness” while serving as a quiet form of resistance.

To belong, we must understand the spiritual bond that strengthens us.

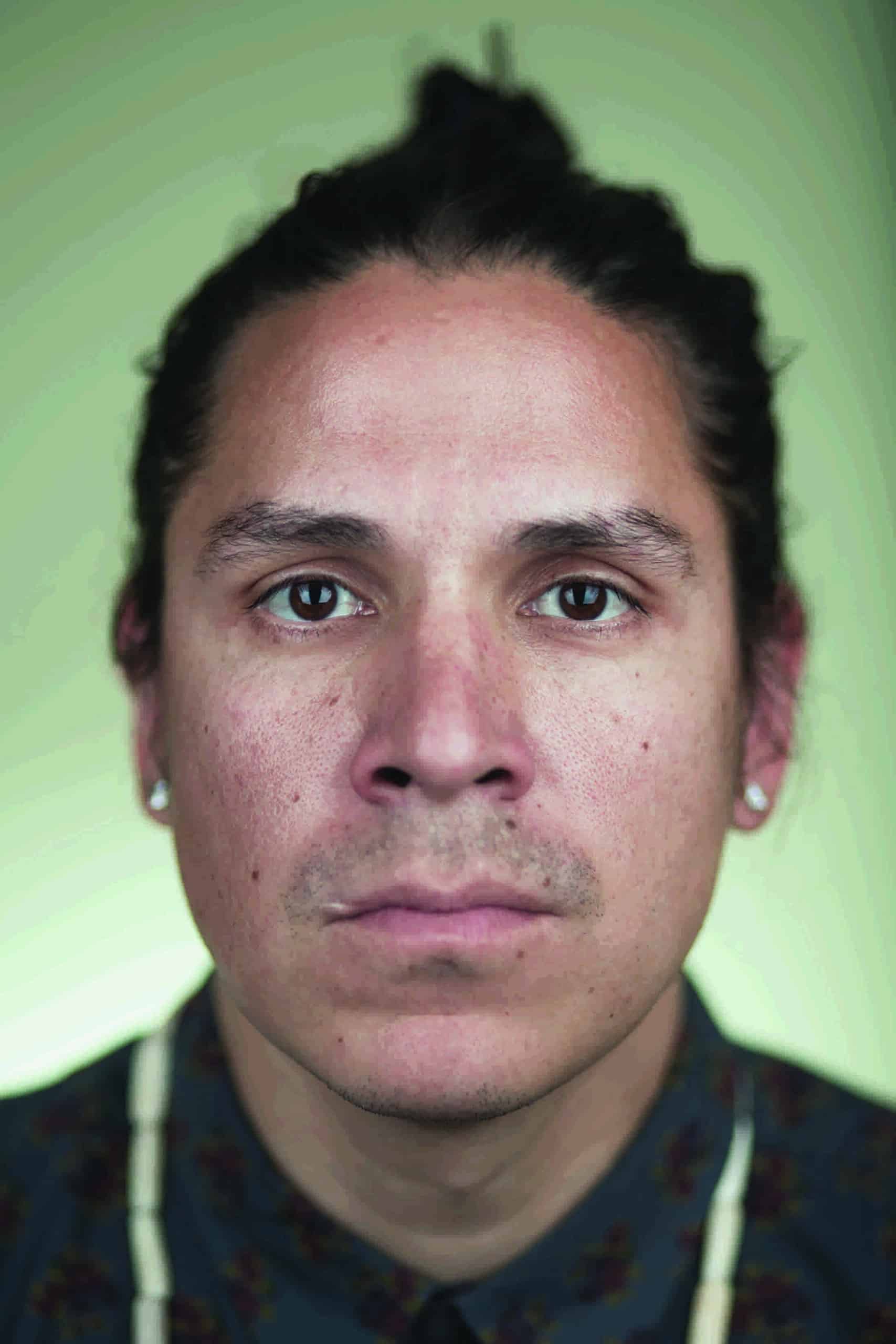

Nicholas Galanin

For artist Nicholas Galanin (Tlingit/Unangax̂), belonging is rooted in place, lineage, and responsibility. “It means connection to the land, to the ancestors and the knowledge they have shared with us,” he says. “It’s understanding the seasonal relationship to sustenance, and the spiritual bond that strengthens us.” That ethos radiates through Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan Parts I and II, Galanin’s captivating two-channel video installation that weaves together traditional Tlingit song and dance with contemporary movement and electronic sound. In the first video, a Tlingit dancer performs to a pulsing, synthesized beat; in the second, a breakdancer moves to a traditional song. The intentional juxtaposition puts the modernity and relevance of Tlingit culture on full display, pushing visitors to rethink what they think they know. “This work is about what’s possible when culture is allowed to grow and expand.”

Galanin, who is based in Sitka, Alaska, comes from a long line of Tlingit artists and has spent more than two decades developing a practice that defies categorization. A graduate of London’s Chelsea College of Art and Design and the Native Arts program at the University of New Mexico, he works across multiple forms of media, including video and installation, jewelry, carving, music, and sound art. His work challenges how institutions and mainstream culture have misrepresented or taken from Indigenous communities and instead offers a forward-looking vision of what Indigenous life and creativity can be. With Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan, Galanin invites thoughtful dialogue. The piece asks viewers to look at Indigenous knowledge systems not as artifacts of the past, but as essential parts of the present. “My work provides an opportunity for understanding,” he says. “It often removes artificial barriers or borders.”

On This Ground’s themes of American belonging, memory, and ownership, have only become more charged since the exhibition first opened. For Galanin, the persistent tension is not surprising. “This is a path many Indigenous communities are historically familiar with,” he says. “Unfortunately, the urgency has not softened, due to increased colonial and imperial violence on both Indigenous communities and Indigenous water and land.” That’s why Tsu Héidei Shugaxtutaan can inspire viewers to see the piece as a testament to survival and adaptation. With its rhythm, motion, and use of language, the piece becomes a kind of bridge between generations, between art forms, and between ways of thinking.