Georgia O’Keeffe translated sun-bleached bones and red cliffs into a modern American mythos. She captured the stark beauty and spiritual resonance of Northern New Mexico with adoration and astonishment. But her gaze—amplified by decades of acclaim and institutional framing—often obscured the deep histories and relationships that Indigenous communities, including the Tewa people, have long held with the land. Tewa Country became known as O’Keeffe Country.

Many communities have called the area home, and continue to do so. The land vibrates with a shared history—a quality you can feel the moment you arrive. Generations of artists—from Agnes Martin to John Sloan—have, understandably, sought inspiration from this land, attempting to capture its beauty and add to its shared story. Yet, in the echelons of American art history, O’Keeffe’s singular mythic voice has remained the most prominent.

So, how do long-excluded voices find their place in the shared story of a shared place? And what does a museum that bears a singular mythic figure’s name do?

At the Georgia O’Keeffe Museum, Bess Murphy is championing the Museum’s commitment to meaningful community engagement. As the Luce Curator of Art and Social Practice, Murphy collaborates with scholars, knowledge bearers, and artists to surface stories that have long been omitted from the record. Supporting roles that focus on making institutions relevant and responsive to the region’s diverse communities is a priority of Luce’s American Art Program.

Murphy recently welcomed us to Santa Fe to experience this community-based work in action.

Bess Murphy. Photo: Jacob Shije for Henry Luce Foundation

“O’Keeffe was never all alone,” Murphy told us in the halls of the Museum. “She was moving into places that have been occupied since time immemorial, that have complex histories and complex layers.”

When she joined the Museum in 2022, Murphy wasn’t sure how doing this “would work.” She knew that many of the artists and cultural bearers who would be critical to telling a more complete history might not know of Georgia O’Keeffe or her work, and might not like either. Murphy also knew that the Museum would be opening itself up to potential criticism.

“Museums don’t like being vulnerable,” she explained, “their whole apparatus is about being a place of authority, and that is not vulnerable.” However, Murphy told us she has been pleasantly surprised: “Everyone has had to step into that space [of vulnerability], both at the Museum and the collaborators, and the way that we’ve been able to support each other has been profound.”

We spent the previous day in local artists’ studios, in nature, and in community—experiencing, firsthand, the complex layers Murphy spoke of. Murphy’s charge, in part, is to bring those layers to the Museum’s gallery walls.

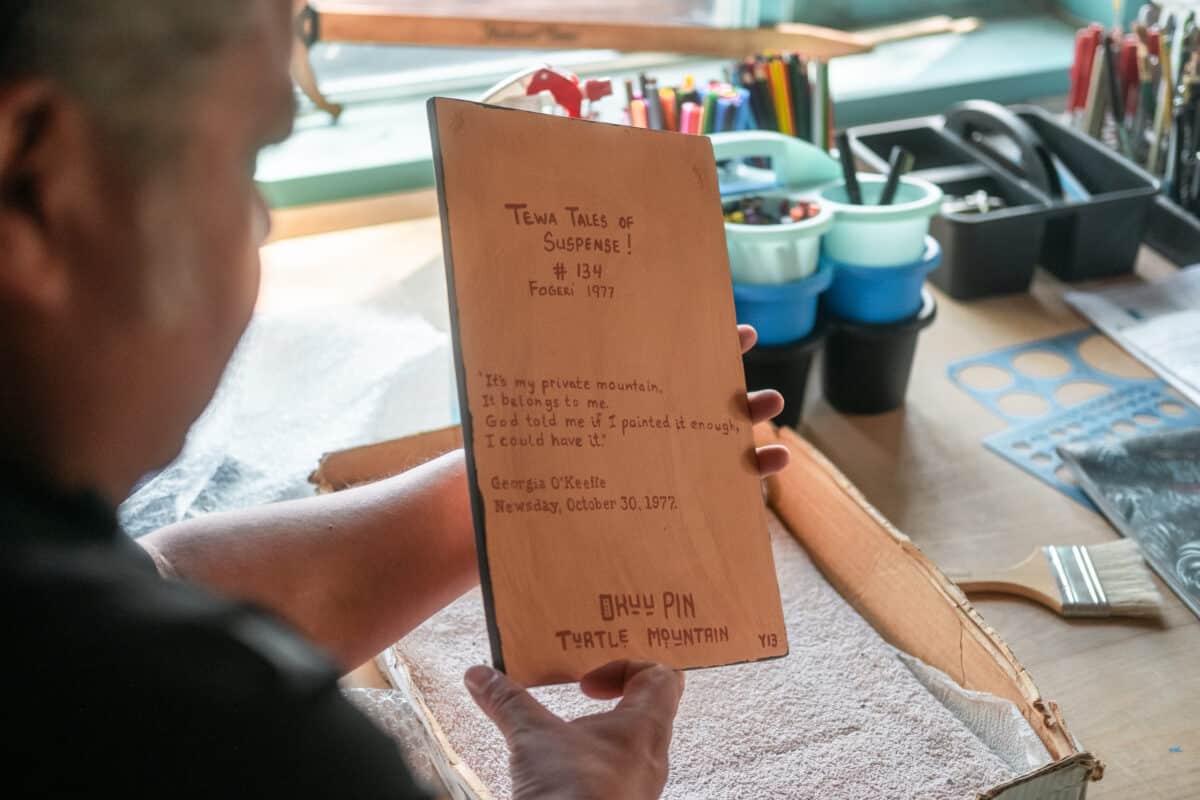

One of the artists, Jason Garcia (Kha’p’o Owingeh), a co-curator with Murphy on an exhibition set to open in November, opened his Santa Clara Pueblo studio to us. He said the collaboration Murphy is championing has been “an affirmation of community.”

Jason Garcia. Photo: Jacob Shije for Henry Luce Foundation

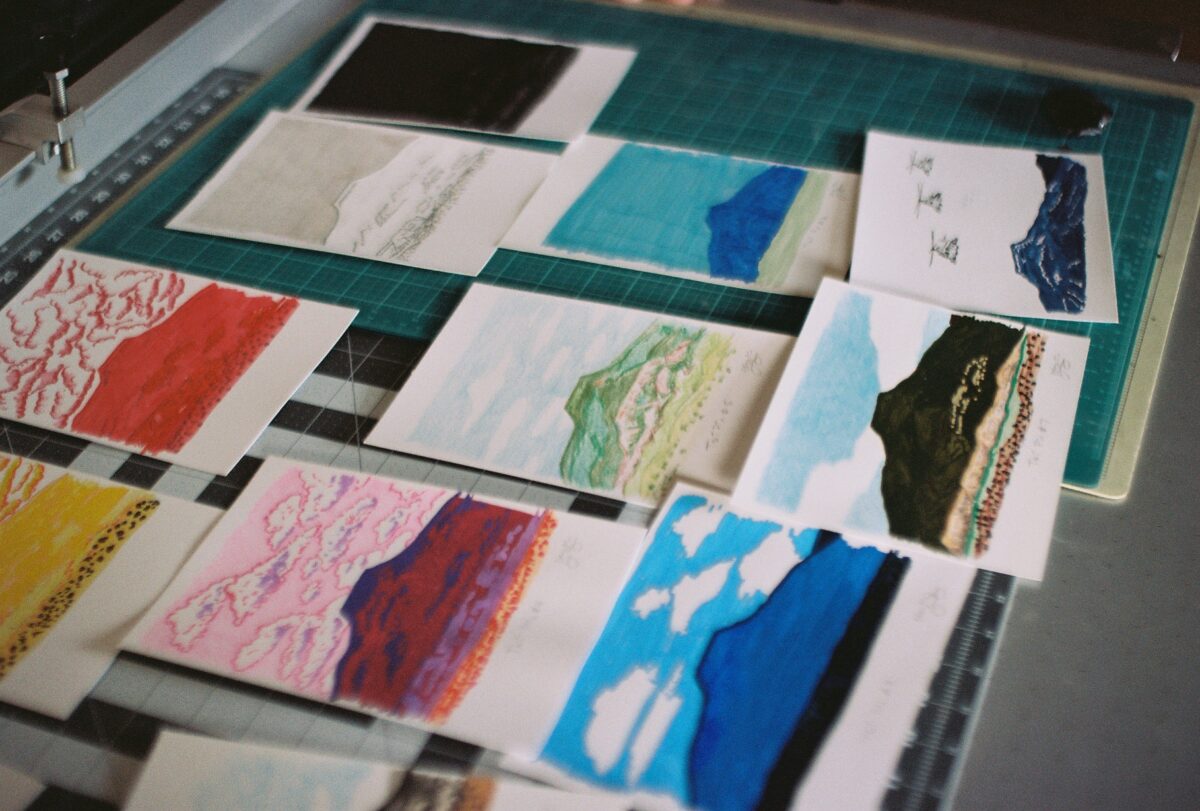

Murphy aims to widen the community when the exhibition Tewa Nangeh/Tewa Country opens. The exhibition seeks to honor Tewa Country while drawing attention to the erasure of the Tewa presence from the story of Georgia O’Keeffe in Northern New Mexico. Jason Garcia and his father, John Garcia Sr. (Kha’p’o Owingeh), are two of twelve Tewa artists participating in the exhibition. Themes of sacred spaces, belonging, identity, and ownership will run through the exhibition that presents O’Keeffe’s art alongside newly commissioned artworks by contemporary Tewa artists.

Garcia Sr. surprised us while we visited his son’s Santa Clara Pueblo studio, which was, it turns out, his studio that he passed down. Sharing space, a creative space, with three generations of artists—Jacob Shije, whose photography accompanies this piece, is Jason Garcia’s son—is deeply emblematic of the work Murphy stewards. Each perspective on art and the shared land their art comes from adds to the conversation.

John Garcia Sr. Photo: Jacob Shije for Henry Luce Foundation

“I always felt that the landscape had a draw,” Garcia Sr. told us, speaking of the natural world that surrounds his family’s homes. He spoke of the mountains, mesas, and waters of Northern New Mexico not as symbols to capture with his brush or a photographer’s lens, but as participants in story, ceremony, and everyday life. To Murphy, this perspective is not only critical but adds to the experience of viewing O’Keeffe’s work.

She wants viewers to “look at an O’Keeffe landscape of New Mexico and see the beauty she painted but also see that there’s something else beyond that.” When visitors view O’Keeffe’s’ Pedernal, Murphy hopes viewers “know that that mountain wasn’t just hers, that it is a sacred site, and that it has all of these other histories to it.”

Exhibitions like Tewa Nangeh challenge the concept of legacy as singular, instead framing it as collective, ongoing, and accountable to place. Through this work, legacy is not a single name etched into art history, but a chorus of voices that resonate in the same key as the ground their stories come from.

Much like the artists of today, Murphy said O’Keeffe was living in community, making in community. “If we keep on just telling the history of Georgia O’Keeffe, then we’re not telling the full history,” Murphy told us. “We’re not even telling the full history of Georgia O’Keeffe.”

The full history of this land—of Georgia O’Keeffe, of the Tewa people, and all of those who have shaped and have been shaped by it—will never be complete. It will continue to add layers with time, with participants, with stories all mingling together. Each new perspective doesn’t compete with the last; it adds to the chorus. As Garcia Sr. said, “She’s part of it.”