Museums nationwide are working to expand and deepen their representation of African American artists and to engage more meaningfully with the communities whose experiences the work embodies. The Henry Luce Foundation’s American Art Program eagerly supports these projects, which range from efforts to address neglected areas of permanent collections to seminal loan exhibitions that recalibrate our understanding of Black artists in the United States. We believe this work has the capacity to significantly revise a dominant American cultural narrative that has long eclipsed African American creative production and the necessary centrality of Black voices.

The Studio Museum in Harlem has done more than any American institution to advance and share the work of African American artists, serving as a vital center for generations of Black art and cultural work. The prospectus the museum published for the opening of the museum in 1968 was expansively visionary: “We must learn to understand the great capacity of art to communicate across a manner of boundaries, not just the lines that divide the past and the present but that separate one way of life from another.”

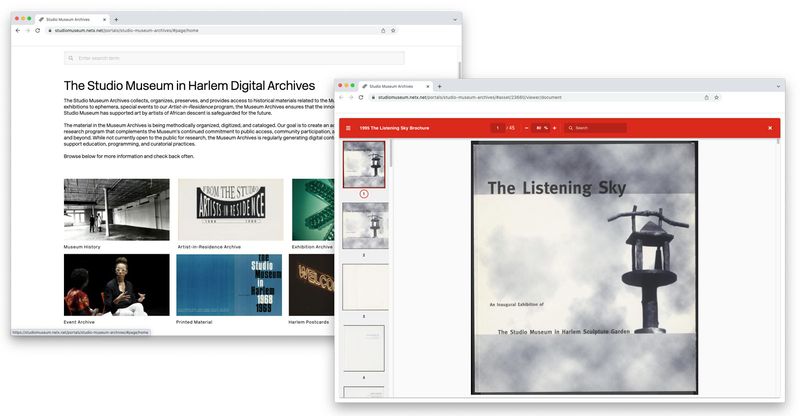

As it prepares to open in a new, purpose-built home in 2024 the Studio Museum is engaged in a compelling deep dive into its past, seeking to more fully understand the range of its work over 50 years and to explore how that history can inform the museum’s current and future activities. To support this work, Luce partnered with the museum in 2016 to support a strategic plan for creation of an accessible museum archive, and in 2017, we provided a major grant for a three-year archives project completed by museum archivist Mimi Lester.

I recently spoke with Dr. Connie Choi, the Studio Museum’s Associate Curator, Permanent Collection, about the outcome of this massive undertaking. She pointed out, “From just a few years after the museum’s founding, its staff understood the importance of retaining archival material—an awareness that no one else was going to tell their story—but until now, it has been completely inaccessible, even internally.” Choi describes the new access for staff to 28,000 archival assets—from curatorial files and installation photos to unpublished brochures and live recordings—as exciting and transformational. A subset of these assets are now accessible to the public through the Archive Portal on the museum’s website.

As they work to create the Luce-supported installation—a rethinking of the 2008 installation Higher Ground: A century of Visual Arts in East Tennessee—KMA staff have entered into deeper and more sustained conversations with nearby partners including the Beck Cultural Exchange Center, which since 1975 has preserved and taught African American history and culture. The museum has high hopes for the more comprehensively inclusive cultural narrative that the new installation will offer. In proposing the project to Luce, Butler wrote, “We embark on this project with the deep conviction that, as a vehicle for community self-examination and self-knowledge, it has the potential to change the way an increasingly diverse community thinks of itself.”

Many of the Luce Foundation’s museum partners are finding ways to new and productive work through deeper dives into the local—working to more fully understand diverse and often obscured histories that can resonate with regional artists and communities of color. These projects also have the capacity to support adjacent efforts, just as KMA’s work is helping to advance the restoration of the Beauford Delaney house and drawing attention to the broader efforts to revive the once-thriving Black neighborhood of East Knoxville where it is located.

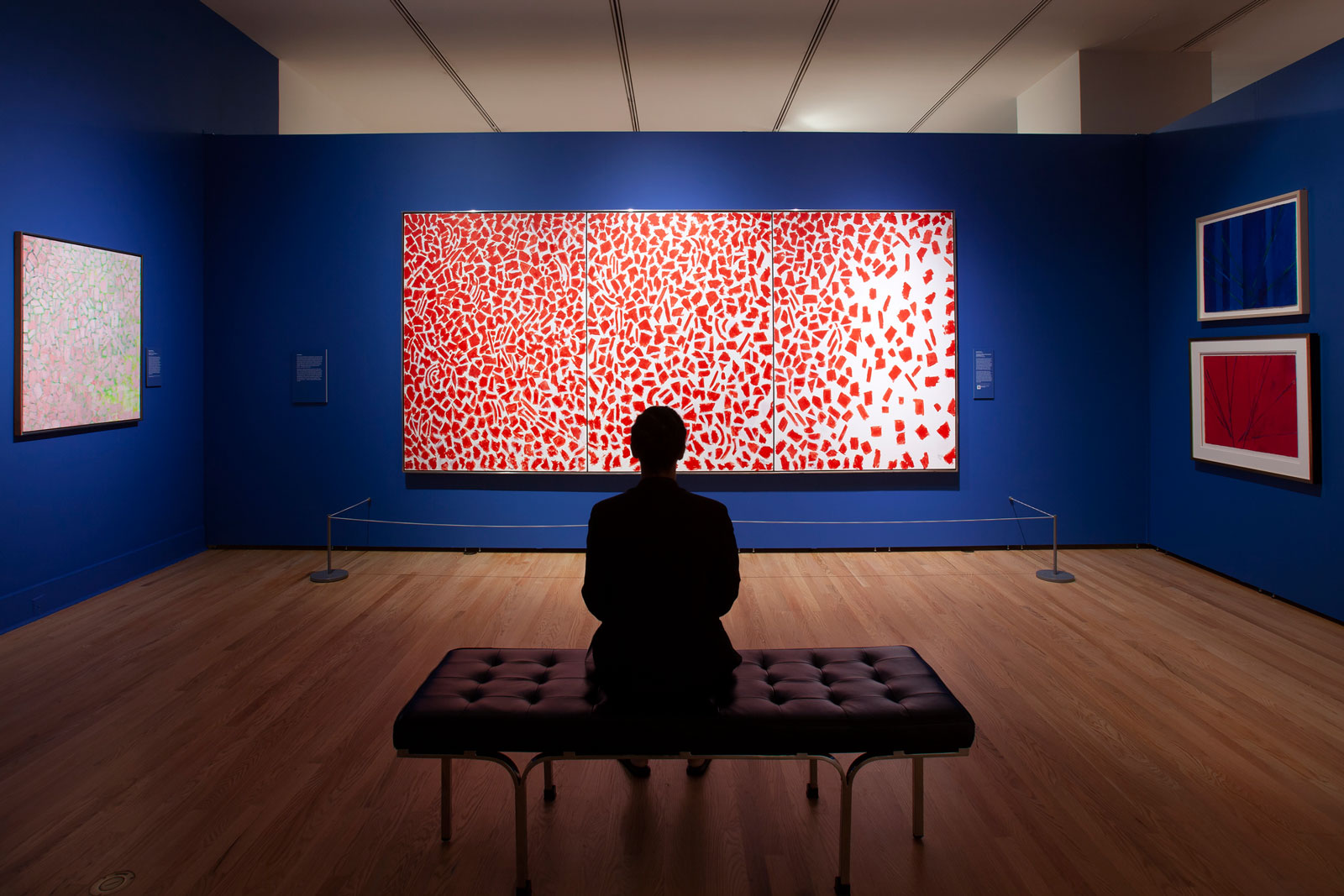

Another exhibition that is still on the road provides an impressive example of how new models of collaboration can heighten the relevance and impact of exhibition projects for local audiences and partner organizations. Alma W. Thomas: Everything is Beautiful, a rare, full-scale retrospective exhibition of the pathbreaking African American abstractionist, was organized by Seth Feman of the Chrysler Museum in Norfolk, Virginia and Jonathan F. Walz of the Columbus Museum in Columbus, Georgia. According to Feman, the exhibition and tour were conceived, “not just as a kit of loans, but as a set of partnerships” that included the additional venue museums—the Phillips Collection in Washington, DC, and the Frist Art Museum in Nashville, Tennessee.

The venues were deliberately chosen because of their relevance to Thomas’s life and career, and for the local partner organizations with which each venue museum could collaborate. The organizations include several historically Black colleges and universities (HBCUs): the Phillips Collection worked with the Howard University faculty members Melanee Harvey and Elka Marie Stevens; and the Frist team partnered with Jamaal Sheets, Director or the Carl Van Vechten Gallery at Fisk University, to illuminate the seminal 1971 Fisk exhibition of Thomas’s work organized by David Driskell.

The geographic placement of the exhibition was key to the success and productivity of the partnerships in each locale. Local cultural histories, as well as Thomas’s own ties to the venue cities, provided fertile ground for audience engagement. Feman added that, beyond race, Thomas’s remarkable interdisciplinarity—spanning everything from puppet-making and clothing design to religion and gardening—provided ready leads through which they established multiple points of entry for their audiences.

These projects exemplify the deliberateness and care with which many of our grantee partners are reconsidering accepted histories and their own institutional practices to foreground and celebrate the cultural contributions of artists of color. They provide inspiring models through which museums can strive for sustained productive collaborations with communities beyond institution walls.

Terry Carbone is program director for the Luce Foundation’s American Art Program.

Choi articulated the dual role of the archive as an internal record of the museum’s work and a resource for the writing of a more public history of the Studio Museum’s role in advancing the work and careers of Black artists. (The first Luce grant to the Studio Museum, in 1984—just two years after the founding of the American Art Program—was for an archive development project, creating a wonderful through line from that moment to the present.) Choi says that now—after recent publications and exhibitions about post-war African American artists have attempted to tell the museum’s history—the Studio Museum is empowered to take over the telling of its own story. Key among the distinctive features of its practice, she adds, was the multiplicity of artistic aesthetics and practices—notably including performance—that it embraced from the outset.

Choi added that artists who have visited the online portal are now reaching out to the museum to build their own personal archives with exhibition histories and installation photos. The materials include the museum’s pre-2000 brochures, including those associated with its revered Artist-in-Residence program which in many cases offered the first critical essays about their work.

Far afield from the Harlem nexus of Black cultural practice, Luce grantees are celebrating African American artistic legacies as part of their work to rediscover collective community histories. Knoxville Museum of Art (KMA) Director David Butler shared that Knoxville’s history is Black history. “Parts of our collective story have been forgotten or, worse, intentionally erased,” he said, referring to the damage done to Black urban neighborhoods at mid-century, in part by the expansion of interstate highways. Referring to KMA’s work, Butler added, “We can’t change that, but there’s much we can do to present a more complex, complete, and balanced picture of the past.”

With that goal in mind, in 2018 the museum began a concerted effort—led by curator Stephen Wicks—to build a collection of paintings by the African American modernist painter and Knoxville native, Beauford Delaney. Delaney had fled the city after the 1919 summer of anti-Black violence that came to be known as “the Red Massacre.” KMA acquired more than a dozen works that formed the heart of the Luce-funded exhibition Beauford Delaney and James Baldwin: Through the Unusual Door, which explored the intersecting creative journeys of these two gay Black men in New York and Paris. Butler and his staff were intentional about engaging partners and communities of color, particularly in the robust programming associated with the exhibition. A key outcome of this seminal project was the decision to entirely reshape KMA’s permanent collection installation to revolve around Delaney.

Sign up for updates

Explore Themes and Ideas