Sarah DeMartazzi, Clare Boothe Luce Program Assistant, shares her reflections after attending “Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Ethics and Religion,” a day of panel discussions hosted by Union Theological Seminary in the city of New York. Since 1836, Union Theological Seminary has been a space for progressive theology, “where faith and scholarship meet to reimagine the work of justice.” The Seminary has many notable affiliations including its neighbor, Columbia University.

On Thursday, January 30th, I had the opportunity to attend the panel discussion “Artificial Intelligence: Implications for Ethics and Religion” at Union Theological Seminary with Carlotta Arthur, Program Director for the Clare Boothe Luce Program. Four panels led the audience through an exploration of artificial intelligence (AI); AI and ethics; AI, ethics, and religious implications; and AI and theological implications.

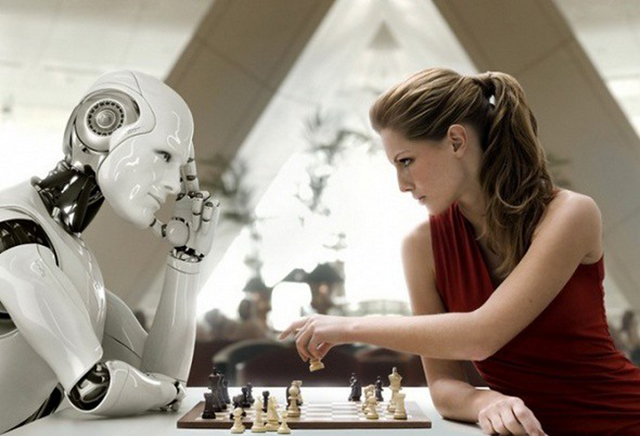

As a previous Ethics & Society post on AI noted, AI is a computer or computation system that models human thought and behavior. Some panelists described AI as a tool designed to help humanity, but unlike other tools, it has the capacity to learn, and that learning isn’t always well understood by humans. As humanity treads down the path of AI and technological development, conversations about where the path leads and the ethical contexts in which it unfolds are necessary. The Seminary’s event provided a space for such conversations, bringing together scholars, religious leaders, theologians, and business professionals to think about humanity’s place within the universe and the responsibilities that come with creating new, wonderous, life-altering, terrifying, and potentially dangerous technologies.

The day’s conversations, by my observation, kept circling back to a single and persistent question, “What makes us human?” and by extension, by creating AI, does that mean we lose some of our humanness and/or can AI be an extension and tool of that humanness? I felt the discussion around ethics and AI spring up from a deep discomfort, not about what AI represents on its own, but about what its existence means for humanity.

No single panelist had an answer to the question “What makes us human?” (nor do I think it possible for one person to have such an answer), and each presenter offered their own puzzle piece. As one panelist aptly put it, “We are the only species that we know of that is so caught up in understanding its own existence.” Humanity angsts over life, the universe, and everything. We want to know there is something more for us, be it a belief in a higher power, the ability to sojourn beyond our galaxy, or all of the above. We are explorers and pioneers. We are finite, emotional, and creative beings. We are also capable of inflicting terrible harm. What seemed to make the room most uncomfortable appeared as much related to the darkness that AI could illustrate about our own nature as it could potentially manipulate or even destroy us. I believe that AI reflects our humanness, both our desires to find greater meanings and possibilities, as well as our darkness, our light, and all the shades of gray in between.

Understanding human nature is essential to understanding our future with AI. From the discussion of humanness arose conversations about governance—If we can’t hold ourselves accountable for wrongdoing and foster ethical behavior, how can we possibly create AI that behaves ethically? Ethical leadership (which will have its own post in the near future) seems the natural and obvious solution for creating this kind of governance, but as the panelists teased out, our leaders don’t always act ethically, don’t always understand the technology they form decisions about, and aren’t always chosen democratically. The panelists elaborated that when institutional systems are built upon capitalistic greed, the system doesn’t always reward people for behaving ethically, and sometimes it mistakenly rewards others for unethical behavior.

So, what do we do? Luckily, the event brought about some uplifting and actionable suggestions before letting its audience back into the world. Panelists argued (and I agreed) that discussions about ethics and technology increasingly need to be embedded within everyday life and conversation, championed by teachers, parents, religious leaders, and peers from diverse backgrounds. I did note, though, that while all of the panels called for more diverse voices at the table, there were very few women or people of color actually represented on the panels, though the audience itself was fairly diverse. I think small events, like the one hosted by Union Theological Seminary, are perfect platforms for increasing diversity and building the world we want to live in. I think, too, that diverse thinking will come in the form of more interdisciplinary discussions about technology, as no part of human life is really removed from technology. As previous CBL blog posts have discussed, social and behavioral sciences should be present in these discussions, helping to guide conversations about human behavior and humanness.

I want to end this post by reflecting on this question: because humanity created AI, it is an extension of ourselves, but in its creation, does AI detract from our humanness? I believe, by its very existence, AI has always been an extension of humanity and not a detraction. AI doesn’t dim our humanness, but casts a spotlight on all of our gems and warts, and thus presents new opportunities for human growth, both personally and spiritually. But with AI comes a Pandora’s Box that we can’t ignore, questions and insecurities emerging over surveillance, privacy, climate change, war, peace, mortality, and immortality. AI and technology force us to face these questions head on, but, as one panelist explained, AI and technology will never be the magic button that wipes away all of our problems. AI is an extension of both our capabilities and our complexities as a species, and it is likely to solve some problems while creating new ones; however, humans seem to love solving problems, and perhaps that is part of who we are, too. Problem solvers and solution makers, yearning for something more.

Author Bio

Sarah DeMartazzi is the Program Assistant for the Clare Boothe Luce Program. Prior to joining the Luce Foundation, Sarah was the administrative assistant for the PCLB Foundation, managing their office space and providing support for their grant cycle. She was also previously a research assistant at the New School and in the law firm of Paul Weiss. Sarah earned a master’s degree from the New School in Politics, focusing on Global Environmental Politics, and she earned her bachelor’s degree at Penn State University in International Relations with a minor in Environmental Inquiry.

Sign up for updates

Explore Themes and Ideas