Asma Naeem: I am Asma Naeem, the Dorothy Wagner Wallace Director at the Baltimore Museum of Art. I’m thrilled to discuss an exhibition that has been game-changing for many visitors so far: Joyce J. Scott: Walk a Mile in My Dreams. It’s a 50-year retrospective of an artist born in Baltimore who has tackled both local and global issues with incredible diversity in language and approach. Joyce J. Scott is a unique figure. She uses jewelry, textiles, beadwork, sculptures, and multimedia installations, creating a beautiful porosity between art and craft. This is deeply rooted in her upbringing—her mother was a remarkable quilt maker, and Joyce learned from her how to turn daily life into art. This retrospective, co-organized with the Seattle Art Museum, features 140 objects from the 1970s to today, and includes some incredible participatory moments, which I’d be happy to share if we have time.

Jackie Edwards: Please do! Why is this exhibition particularly important right now?

Asma Naeem: First, Joyce is an octogenarian and still actively creating. She’s been largely under-recognized throughout her life. Why not celebrate her greatness while she’s still alive? She’s a MacArthur Genius, so she’s received some recognition, but as art historians and curators, we don’t often do this enough. At the Baltimore Museum of Art, we aim to showcase artistic excellence across diverse backgrounds, and Joyce challenges the hierarchies of both the art and museum worlds in profound ways. This exhibition aligns perfectly with our mission to uplift and give a platform to Baltimore artists. There’s no one more deserving than Joyce J. Scott.

Jackie Edwards: It must be exciting to showcase a local artist of her caliber in her hometown. Can you tell us more about the inspiration behind this exhibition? How did it come to be?

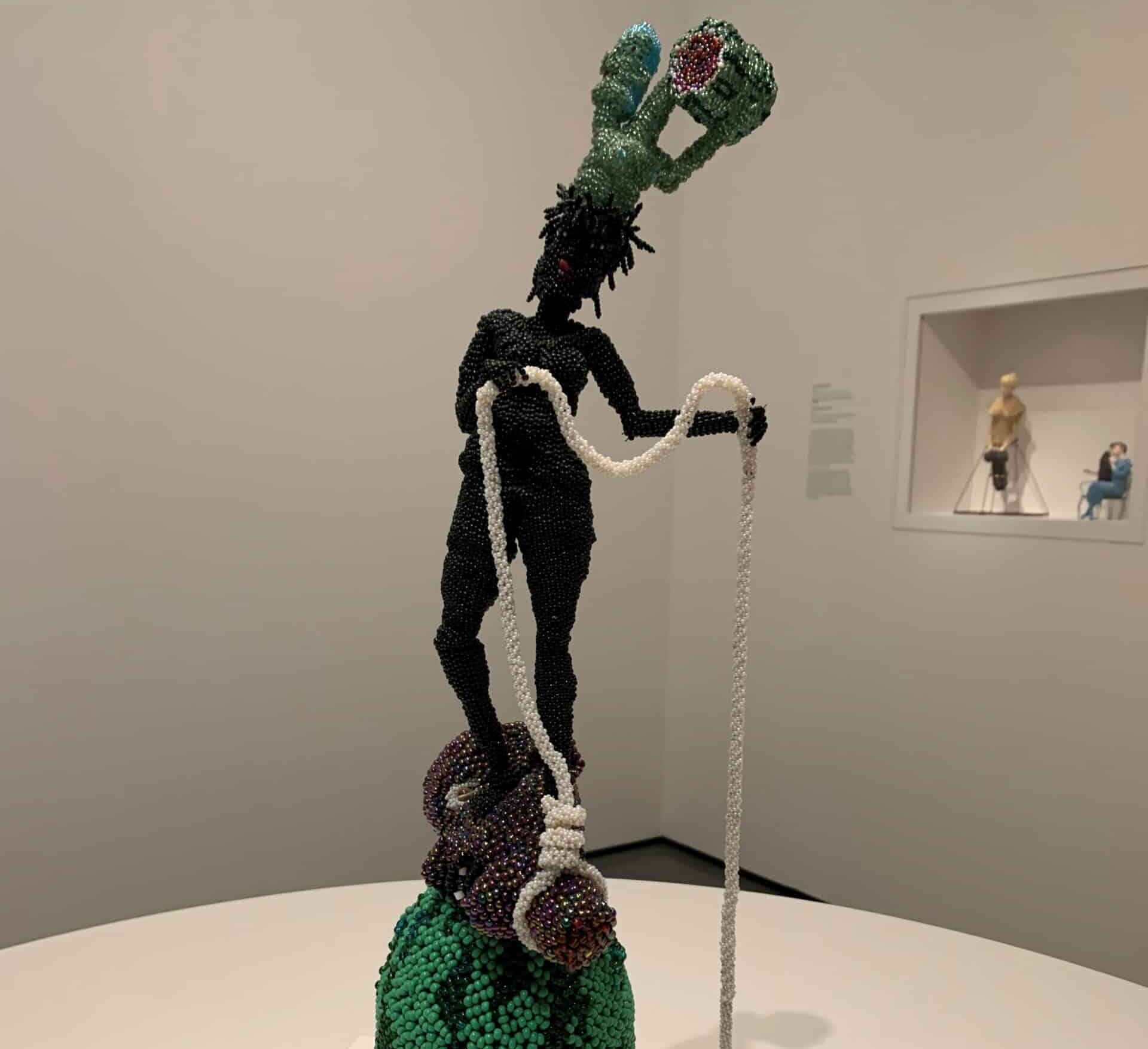

Asma Naeem: Absolutely. We first showed Joyce’s work in the early 2000s, and it was incredibly well received. Since then, we’ve been building a repository of her work that is unparalleled. The BMA is already home to the world’s largest public collection of Henri Matisse, and we’ve been intentional about creating a similar repository for Joyce Scott. As we worked towards that goal, we realized there was so much more to share with the public about her art. Joyce has grappled with some of the most profound social justice issues—apartheid, racist stereotypes, and more—using her own language to address difficult conversations. She explores race and the legacies of slavery with humor and sarcasm, making her approach incredibly unique.

Jackie Edwards: Given that balance of humor and heaviness in her work, how has the audience responded?

Asma Naeem: The reactions have spanned the spectrum. There are moments where you can see visitors’ “aha” moments as they approach what seems like a beautifully beaded object, only to discover a deeper narrative as they get closer. We’ve seen laughter, we’ve seen tears—I’ve personally experienced that full range of emotion. Joyce’s performances, like Thunder Thigh Review, challenge assumptions about Black bodies, especially Black female bodies, in powerful ways. Her ability to intertwine sadness with joy is captivating. For example, in her later work, she incorporates dice into her sculptures, symbolizing the randomness of life—what family you’re born into, the histories you carry—but ultimately, what you choose to do with your life is up to you. It’s a powerful message of overcoming the past and embracing shared humanity.

Jackie Edwards: That sounds incredibly moving. Was there a specific audience you had in mind when developing this exhibition?

Asma Naeem: We hoped to attract those who have followed Joyce throughout her career, as well as younger artists who may have only recently discovered her work. What’s been wonderful to see is the range of visitors—art lovers, craft enthusiasts, and especially young artists—who have paid tribute to her, often through social media. Joyce’s hybridization of identities and cultures resonates deeply with the current generation, particularly as contemporary artists blur the lines between traditional materials and craft.

Jackie Edwards: You mentioned participatory moments earlier. Could you elaborate on those?

Asma Naeem: Certainly. One gallery features a large loom where visitors can contribute by weaving their own threads into a collaborative tapestry. It’s been wonderful to see people of all ages engaging with this space, adding their personal touches to the piece. We’re raffling some of the finished tapestries and may even acquire the largest one for the museum’s collection. It’s truly special to witness different generations interact with this element of the exhibition.

Jackie Edwards: That interactive aspect must be thrilling, especially for an artist like Joyce who blends performance and craft. Is there an essential experience or takeaway for visitors to this exhibition, and will that translate to Seattle?

Asma Naeem: I don’t think there’s a single takeaway, but there are several recurring motifs throughout her work. For example, the needle and thread—one of her most powerful symbols. In the first room, you’ll see a structure we call “the yurt,” which is covered in beaded work, with a woman atop holding a large silver needle. That needle connects to various hands of different skin tones, symbolizing different ethnicities and backgrounds. The needle reappears in other works, linking her family’s history as sharecroppers to her art. This weaving of past and present is a central theme throughout the exhibition, and it’s something that will resonate in Seattle as well.

Jackie Edwards: That’s such a meaningful perspective for visitors to keep in mind. Do you have a personal connection to any of her works that will stay with you after the exhibition?

Asma Naeem: Absolutely. Joyce makes me want to be a better person. Her openness to life’s experiences—good and bad—is inspiring. She doesn’t wallow in the traumas of the past; instead, she learns from them and moves forward with hope. Her wit, her wisdom, and her cheekiness are unforgettable. She has a way of turning dark humor into something deeply profound, and I’ll always treasure my interactions with her and her work.

Jackie Edwards: What a beautiful takeaway. It sounds like hope and wisdom can only come from a life rich with experience.

Jackie Edwards is the Program Associate for the Luce Foundation’s American Art Program.

This American Art Program interview series explores the minds behind museum curation. In each interview, our American Art Program grantees share the curatorial choices behind their exhibitions and how these align with the Henry Luce Foundation’s mission to foreground American art as a catalyst for dialogue and understanding, celebrating creativity, exploring differences, and helping forge common ground. This interview has been edited for clarity and brevity, and an accompanying video takes you on a visual journey.

Sign up for updates

Explore Themes and Ideas